Hi 396,

I was looking through each of the tools for digital history research, and Omeka caught my eye. I enjoy looking at timeline projects as I find having that visual component can make a considerable difference when interpreting data. An example of this is our guest speaker Benjamin Hoy and his Building Borders project. When one simply looks at data without a visual component, it means almost nothing to someone not in the field. In a way, creations like Omeka have opened up a platform that academics and regular web users can both interpret. Another component that influenced me to look into Omeka is its broad platform that is used by multiple different institutions to fit a variety of purposes. My trials and comments about the online tool are below.

Omeka is a tool that was created by developers at the Roy Rosenzweig Centre for History and New Media at George Mason University in 2008. It is an open-source web publishing platform that caters to many different purposes. With Omeka’s friendly design, institutions such as museums, libraries, archives, and collections of scholarly merit use it to create galleries and exhibits that can properly showcase its array of information in a chronological or taxonomical referencing system. Since it is set up for mostly public use, Omeka’s design is quite simple to understand (and I am as stubborn and inexperienced as one can get with anything digital, so this says a lot) and offers a variety of plugins and themes that are easily customizable to suit the needs of ones project aesthetic. Omeka relies on a strong metadata standard for find-ability and search-ability, which is one of its strongest components. Metadata (to which I will admit, I had no idea about until a few weeks ago) is data that provides data about other data – which doesn’t sound confusing at all. Descriptive metadata is the most important kind in the types of cataloguing and classifying that one would want to have in a digital archival setting. When metadata is entered fully and properly, it is a wonderful asset for platforms such as Omeka.

The issue that arises with Omeka, then, is not so much the metadata and its use, but instead the way we compile and edit the metadata. I learned this (and what metadata is) when our class took a trip over to the Digitization team at the University Library. There can be sloppily done classifying, which is not the programs fault, but its user. When one uploads an image into Omeka’s database, it gives the user four different areas where they can classify the image. Starting with Dublin Core, which is the metadata element to all existing Omeka records. It allows input to the name of the given source (title), the topic of the source (subject), a visual account of the source (description), a related source from which the original source is taken from to begin with (source), the company that holds certain copyright over the source (publisher), the time in history associated with the event of the source (date), and then more in-depth areas for classification such as contributors, rights, relations, format, language, type of resource, identifier, and coverage. Item Type Metadata is the second tab, which asks what type of image is being brought into Omeka, with categories such as still image, text, website, database, hyperlink, etc. Once one of these options is clicked on, a corresponding set of tabs will open up to codify the source further. The third tab is Files, and it is where one would attach the source into a display order that is preferable for the projects intentions. Lastly there is Tags, which is the final step in systematization – attaching key words that are in relation to the source used. Once all of the data is placed into these four steps and saved, one can go into a few different tabs that organize the created project: browse items, browse collections, browse exhibits, and an about tab.

Omeka is a great tool for what I have explored of it so far. It is relatively easy to use, a useful formatting for cataloguing and classifying source materials of different media, and allows a large population of web users to understand its system without having coding experience. Since I am a very new user to this platform, it was difficult to find limitations with how it is organized, so I had to do some looking online for what others believed were the weaknesses of the tool. Besides the usual limitations most programming websites offer – only a set amount of plugins were free and many others had to be purchased on a yearly plan, there were only a few limiting factors of the program. Omeka is apparently not able to be integrated with Javascript into a coherent element.

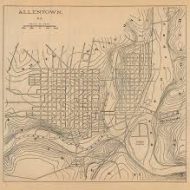

Histories of the National Mall is the first website that I explored that uses Omeka. It offers historical maps in colour, and gives information on the mall’s history. Another interesting project I stumbled upon is called the Intemperance project. It is a digital project that details cocktail culture in New Orleans, Louisiana. This one was quite progressive in the way that it seamlessly scrolls through a detailing of the project, the map that shows prohibition from 1919 and 1933, and then a browsing section to look through the entire database. I did find quite a few websites that were outdated, but this can be the fault of the creator for not updating their projects.

That is all I have on Omeka for now.

Best,

Meagan Laurel Power

Thank you for providing a detailed look at how you create an object in Omeka with metadata. Is Omeka first and foremost about creating galleries and exhibits? Or is it a digital archive? Or something else? Or all of the above? Is this lack of clarity a problem with how they describe the project?